No treatment or vaccine is risk-free. So the key question is whether it does more good than bad. Regarding the AstraZeneca vaccineBoth the MHRA and EMA reviews reaffirm that the benefits continue to far outweigh the risks.

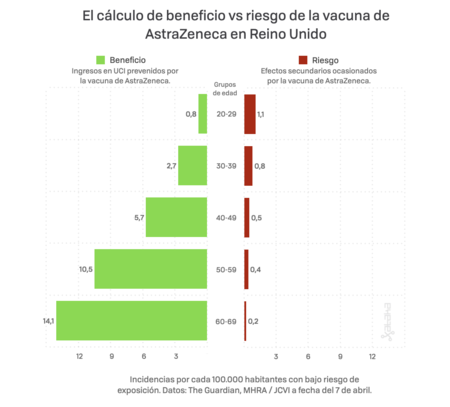

However, the risks are not the same for all age groups, so the cost-benefit calculation varies (although in all cases it is always favorably inclined towards profits).

More factors than we can calculate

The risk of dying from an episode of thrombosis after vaccination it is extraordinarily small, about one in a million. Many daily activities, and also the prescription of many medications, carry greater risks than the AstraZeneca vaccine.

By contrast, COVID-19 kills one in eight infected people over the age of 75, and one in 1,000 infected at age 40 among those who develop symptoms.

However, those under 30 are much less likely to die from COVID, and it is precisely in younger people where the risk of developing a thrombus after vaccination increases (probably because, being a consequence of a hyperreaction of the immune system, this is more rare in older people whose immune system is already in decline).

This situation has made many wonder if the cost-benefit calculation is really so clear among the younger population.

The truth is that we do not know enough to be able to enter the data in a calculator and obtain a simple and exact answer to a question like: if I am 23 years old, what is the risk of dying if I am inoculated with AstraZeneca? To this question you have to introduce many proxy variables of the type:

- How likely a person is to be exposed to the virus (for example, how prevalent is the virus, locally, at that time; what is their occupational exposure; etc.)

- How likely it is that one will suffer medical complications as a result of contracting the virus, which is mainly determined by factors such as age, but also by underlying health conditions.

The potential benefits also accrue each day the person is vaccinated (and exposed to the virus), so there is no static response over time.

In order to simplify, therefore, the revision of the EMA has chosen to examine the estimated number of ICU hospitalizations avoided by the vaccine (by age group). It has also been chosen to illustrate three possible levels of exposure to the virus, linking them to the benefits accumulated over 16 weeks.

Specifically, to estimate the potential benefit, incidence rates based on the Covid-19 Infection Survey, ONS, of April 1, 2021, have been taken into account. The proportion of hospitalizations in a cohort has been calculated using the estimates of the COVID-19 hospitalization rates associated with 10-year age cohorts. A fixed vaccine efficacy of 80% was also used for all age groups for ICU reduction.

To calculate the potential damage, the number of cases of thrombus reactions provided by MHRA until March 31 in five-year age ranges has been taken into account.

Thus, these graphs show the approximate risk for people of different ages, during 16 weeks, to three different exposures to the virus (which would depend on the local prevalence of the virus and how much an individual was exposed to other people who could be infected). Naturally, people with underlying health conditions, who will be at increased risk of a poor prognosis if they become infected with COVID-19, should have a greater benefit from the vaccine.

It is very important to note that the benefits shown are approximate, taken at a constant level of exposure to the virus for 16 weeks. It must also be remembered that a vaccinated person will continue to accumulate this benefit during the lifetime of the vaccine protection. The risk of vaccination occurs only at the time of vaccination. This means that, over time, the benefits will increase but the risks will not.

It is also important to note that the benefits listed are only for ICU admission due to COVID-19. For every person listed as saved from ICU admission, there are many more who could be saved from hospitalization and the long-term effects of having been through COVID-19. Nor is it showing the huge benefit of not transmitting the virus to others, increasing the risks overall.

All these factors make any decision to be made about the AstraZeneca vaccine is very complex: the risk-benefit ratio varies between different people and as the prevalence of the virus changes, and we also have to simplify many variables because we do not yet know how to estimate them accurately.

All in all, and in general terms and with the data we currently have, we can rest assured: the EMA has established that the benefits of vaccinating with Astrazaneca far outweigh the risks by age group.